Wild Stories

about the great outdoors

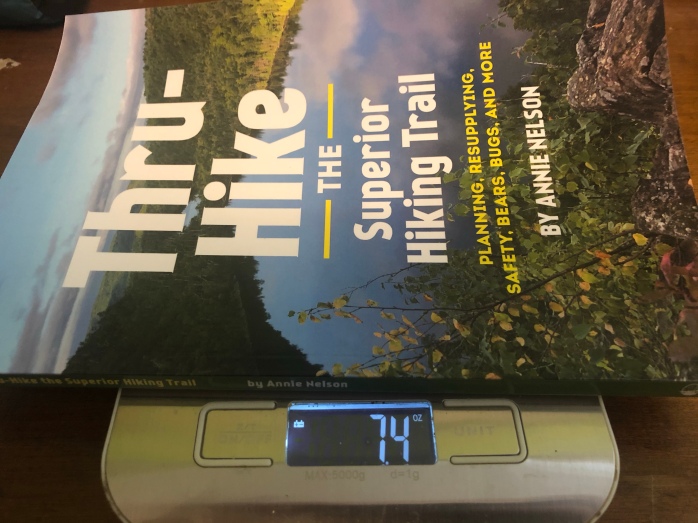

SHT Thru-Hiking Guide now available in Print

I’m thrilled to announce the print version of my thru-hiking guide for the Superior Hiking Trail is now available. “Thru-hiking” a trail means hiking an entire trail in one hike. In the case of the Superior Hiking Trail, that means spending 2-4 weeks hiking more than 300 miles through rugged terrain with sweeping views of Lake Superior, endless boreal forests and close encounters with wildlife.

Thru-hiking the trail is a dream of many hikers and an extraordinary accomplishment.

To purchase the print version of guide, visit the SHT Thru-Hiking Guide page on this website. The Kindle version is also available on that page. The print version is also available for purchase from my publisher, Northern Wilds Media. Thank you Shawn Perich and Amber Pratt for all your hard work! You’ve made this backpacking writer incredibly proud to be the author of this beautiful guide.

This guide provides a thorough and easy to understand overview of how to plan a trip on the SHT from someone who did it the right way. It’s written for thru-hikers, but the information is useful for day hikers and overnight backpackers too.

Jaron Cramer, development and communications director of the superior hiking trail association

Welcome future thru-hikers!

Thru-hiking the first time Superior Hiking Trail changed my life. My gratitude for that experience spawned a desire to help others successfully thru-hike the trail. I channeled my experience as a long-distance backpacker and a former journalist to bring you a guide that will save you time, money, and stress.

How to plan your thru-hike

My guide offers advice on how to figure out how many miles to hike each day, how frequently you’ll need to resupply, analyses of the trail and the pros and cons of hiking northbound or southbound, and how to include the Duluth section of the trail, which many thru-hikers avoid due to the 54-mile stretch without free SHTA campsites.

The guide advises readers how to gauge their average hiking speed (miles per hour with breaks) and use that to inform their daily hiking goal.

Readers are also taught how to transform their daily hiking goal into estimating how frequently they will want to go into town for more supplies and food.

For the Duluth section of the trail, readers are given a listing of suggested accommodations, none further than 1.8 miles from the trail, along with list of contact information and prices.

“When people think ‘Minnesota,’ they don’t think ‘mountains,’ but after hiking the Superior Hiking Trail, that changes,” I write in the guide.

I give an analysis of the trail’s elevation changes and overall ruggedness by section to help hikers anticipate which stretches of trail will challenge them more, as well as the different logistics to hiking northbound or southbound.

“To maintain the frenetic pace of our everyday lives, it’s hard to avoid developing a frantic outlook on time. If you can force your mind to let go of worrying about deadlines and just focus on putting one foot in front of the other, your confidence will grow with each step,” I write in the guide.

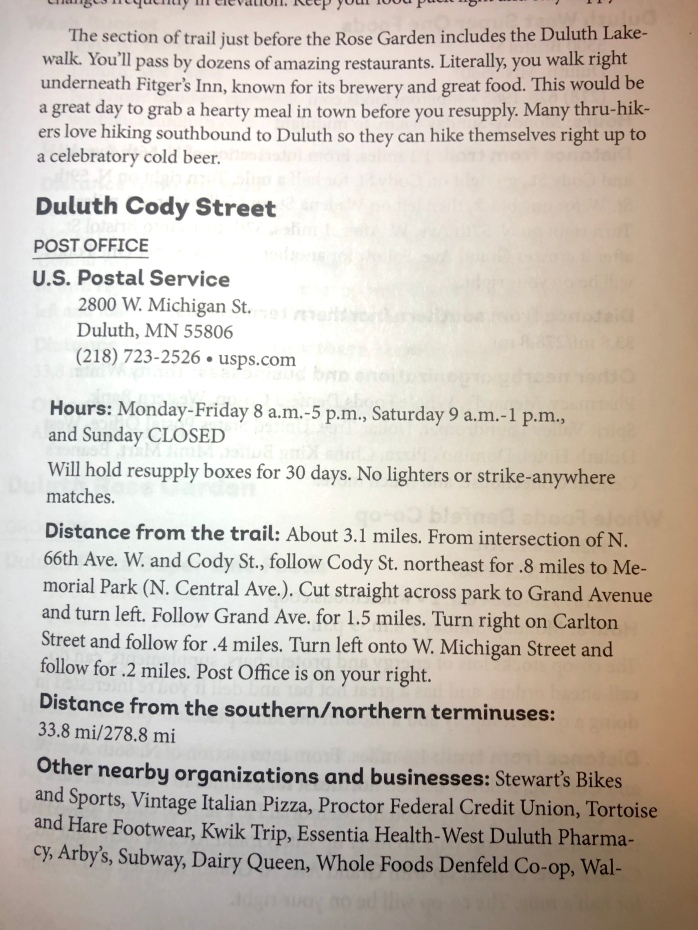

A Yellow Pages for the SHT

Save yourself weeks and months of researching what trail towns have a grocery store, laundromat, and post office. “Thru-Hike The Superior Hiking Trail” includes two charts of all the towns along the trail in both northbound (NOBO) and southbound (SOBO) order, as well as what amenities are available in town like grocery stores, post offices, laundromats, and even includes information like which stores carry which types of cooking fuels.

I believe this list is worth the purchase price alone due to the time it will save readers, as well as the flexibility it offers to thru-hikers while on trail.

Needing to change your plans due to weather, injury, or just hiking faster or slower than you anticipated is the norm, not the exception. Bringing this list with you during a thru-hike will make changing your plan easy and stress-free.

The list includes:

- business addresses,

- phone numbers,

- websites,

- hours of operation,

- distances from the trail,

- walking directions from the trail,

- distances from the northern and southern terminuses,

- other nearby businesses and organizations (churches, restaurants, etc.),

- businesses that are willing to accept resupply boxes and how long they’re willing to hold them,

- and much more!

Save yourself from attempting trail math with a bad case of “hiker brain”

During my second thru-hike of the SHT in 2019, I realized the thing I most wanted was just a list of the campsites on the trail, and the distances between them. The SHTA’s Guide to the Superior Hiking Trail is written for all kinds of hikers from day hikers to section hikers to thru-hikers. Many of the section descriptions include the mileage of spur trails. For example, the section between the Kadunce River Wayside to Judge Magney State Park included an extra .7 miles of spur trail that thru-hikers don’t hike unless they decide to go down the Kadunce River Wayside for some reason.

Calculating your mileage for the day involved adding up distances between campsites, which were spread out in the guide and involved a lot of flipping back and forth. The Superior Hiking Trail Association has since released a new Databook that includes a condensed list of the distances between campsites. I added a similar feature to the print version of my guide after my second thru-hike.

I love the new Databook and am a hiker who believes thru-hikers should acquire every available information resource ahead of their thru-hike. Knowledge is power and will increase your chances of having a successful thru-hike. The one way my campsite list differs compared to the Databook is that I include a list for both northbound and southbound hikers whereas the SHTA’s Databook’s list goes southbound only. It’s pretty easy to do the math, but it’s still requires northbound thru-hikers to do trail math with hiker brain, a profound loss of cognitive function due to hiking-induced fatigue. The struggle is real. I always joke that my IQ drops 50 points by the end of a week on trail.

Additional features

- Navigating the trail

- Safety information specific to the conditions and dangers you’ll face on the Superior Hiking Trail (including interviews with local Search and Rescue squads with decades of experience in the area)

- Advice on how to complete a “Total Thru-Hike” and include the Duluth section of the trail, which does not have free campsites (including suggested itineraries and accommodations for people hiking 10 and 20 miles per day)

- Transportation to, from and on the trail

- Gear recommendations

- Tips for coping with bugs and wildlife

- Tips for easily following the Leave No Trace Seven Principles

- Stories from author Annie Nelson’s 2017 and 2019 thru-hikes

- and much more!

A thru-hike can gift a profound connection to nature

“I learned a lot of practical things on trail: how to manage being plagued by bugs, keep my body happy, and throw a bear bag rope with precision. I learned that I love to hike in the rain when I’d dreaded the idea, that the night noises of the woods become as familiar as the creaking of an old house. I reveled in the capability of my body to wander great distances.

“I also gained a powerful connection with nature that I suspect will shape the rest of my life,” I write in the guide.

I want you to thru-hike the Superior Hiking Trail and fall ferociously in love with the Northwoods. I want you to lust for the trail like I do. My reconnection with nature has added incredible meaning to my life. I wish that for you too.

I also hope you to become a powerful advocate for this trail. I want you to donate to the SHTA, and come to view lopping brush as an act of trail magic. I hope you help all of us who love this trail protect it for generations to come. That’s why I’m always available to any would-be thru-hikers. If you have any questions about this guide or about thru-hiking, please send me an email through this website.

“This book is worth every penny and then some. I see questions posted all the time in online forums that Ms. Nelson answers in this book, and answers better than most online responses do. (…) It’s proving far more helpful than I imagined.”

Todd Mitchell, Canby, Minn., 2019 SHT thru-hiker

For kids who want to thru-hike

Whenever my schooling horse, Zippity, took off at a full gallop, my heart hammered with wild glee. A former race horse, he ran like the wind; it was the closest I’ve ever come to flying. I was a lucky kid. My mom sacrificed a lot to pay for those horseback riding lessons during my childhood, and I am grateful.

My mom gifted me and my sister with tons of amazing enrichment experiences as kids, but she loathes camping. We went car camping a couple times when I was a kid, but not backpacking.

I wish now that I’d discovered my passion for backpacking and wilderness trips as a kid. I didn’t start backpacking until I was 30 years old. I wonder how my life would’ve been different if I had started backpacking at a younger age? Would I have thru-hiked the Appalachian Trail or Pacific Crest Trail after high school or college? Would I have chosen a different college major and career?

Many parents consider extracurriculars like sports and clubs to be a crucial part of their child’s education, not just what they learn in school. I invite parents and kids to add a wilderness trip, not just car camping, to the list of basic life experiences every kid should have as part of a well-rounded education.

What do I wish I had known and done as a kid to become a thru-hiker at a younger age? This blog post tries to answer those questions, and offers some tips and advice for young hikers who are starting to dream of thru-hiking some day.

What are backpacking and thru-hiking?

Many kids have gone “car camping” with their families or friends already. You load a huge tent, a bunch of sleeping bags, and a cooler full of food into the car, and off you drive straight up to your campsite. With backpacking, you load your tent, sleeping bag and food into a backpack and hike miles to your campsite. During a week of car camping, you get to know one place very well. When backpacking, the whole forest is your playground.

Thru-hiking is backpacking an entire trail. Some trails are incredibly long, more than 2,000 miles, and take months to backpack. Some trails are shorter, a couple hundred miles, and can be thru-hiked in a couple weeks.

Where’s my owl?

As a kid, I read every adventure story I could get my hands on: Ursula K. LeGuin’s “Earthsea” series; J.R.R. Tolkien’s “Lord of the Rings” books; and, of course, J.K. Rowling’s “Harry Potter” series. I knew these books were fiction, but I secretly waited for an owl to show up outside my window with my Hogwarts acceptance letter. I never got to befriend a dragon or become a wizard, but I did find a way to go on epic, magical adventures in real life: thru-hiking.

It is delightful to come face to face with a porcupine, skunk, or a curious garter snake. I’ve learned many animals are just as curious about me as I am about them. When I stand beneath a giant tree hundreds of years older than me, it casts a spell of awe. When I climb up a mountain, I feel like if I just knew the right words to say I could grow wings and fly. Real life magic.

Four-Step Checklist

Now that I’ve convinced you thru-hiking is magical, and you’re determined to do it someday, here are four steps for making a thru-hike happen during your life.

- Start backpacking now with your family, friends or youth groups

- Convince your parents to let you thru-hike

- Learn to make and save money

- When to thru-hike

Start backpacking now

Thru-hiking is a skill like any other that gets better the more you practice. The more backpacking experience you get now, the better your chance of thru-hiking later in life.

If you have never backpacked before, start with an easy to follow trail at a state park, as there will be rangers on staff 24 hours a day in case you need help. In Minnesota, several state parks have backpacking trails campsites including Afton State Park, Wild River State Park, Cascade River State Park, and many others.

Start small: Rent gear from a store like REI and take a weekend trip to a state park. Plan to hike only a few miles per day your first trip, maybe four to six miles. Your goal for this first trip is just to figure out whether or not you enjoy backpacking. Your second goal is to learn the basics: using your maps and guides, how your pack feels, how to hike with a heavy backpack, how to set up tent and use your other gear. Parents, the American Occupational Therapy Association recommends a child’s school backpack never weigh more than 10 percent of their body weight. Applying the same weight ratio for outdoor backpacking is probably a good idea.

Once you feel comfortable with the basics, next try a week-long trip on the Superior Hiking Trail or a more rugged, backcountry trail in your area.

If your family doesn’t go camping or backpacking, there are many youth groups that offer the opportunity. Consider joining the Scouts BSA or Girl Scouts of the USA, both of which teach many outdoor, camping, and backpacking skills. There are also a bunch of backpacking camps. In Minnesota, YMCA Camp Widjiwagan and YMCA Camp Menogyn offers several backpacking camps. Another organization, Outward Bound, offers many incredible trips all over the country that range from 4-day trips to an entire semester in the wilderness. Overnight camps can be very expensive. Most camps offer a scholarship program, meaning you can qualify for financial assistance with the cost of camp. The YMCA and Outward Bound offer scholarships for their backpacking programs.

How to convince your parents to let you thru-hike

“Curiosity is not a sin… But we should exercise caution with our curiosity….”

Albus Dumbledore

Your parents love you. Their No. 1 job is to make sure you are healthy, happy, and safe. Even though I am in my 30s and a grown adult, during my thru-hikes I have met a lot parents who told me they wouldn’t let even their adult children go on a thru-hike.

Don’t be surprised or discouraged if you tell your parents you want to thru-hike someday, and they say no, at first. The idea of letting a child, even an adult child, go off into the wilderness for weeks or months, is super scary.

You probably won’t be able to thru-hike before you’re an adult. It’s dangerous. If you’re determined to thru-hike before you’re an adult, invite one of your parents or your entire family to come with you. More and more families are thru-hiking long trails together, like the Strawbridge family on the PCT and the Crawford family on the AT. If your parents don’t want to come with you, see if they’d be willing to let you thru-hike a shorter trail close to home once you’re a teenager. I believe the youngest person to solo thru-hike the Superior Hiking Trail was 15 years old.

You can also start improving your outdoor safety skills. Take classes with your parents so they can see you learning and mastering these important skills. Here are the basic skills I think every thru-hiker should have, kid or adult:

- Map reading

- Navigating with a map and compass

- Using GPS

- Wilderness first aid

- Building fires safely

- Filtering water

- Cooking on a camp stove

- Keeping your food safe from bears and other animals

- Leave No Trace Seven Principles

- Researching the trail, forest and potential dangers of any area in which you plan to backpack

As you grow up, if you can demonstrate to your parents that you are taking your safety and wilderness skills seriously, this will improve the chances they will fully support your dream of taking a wild adventure someday.

Learn to make and save money

Another reason your parents might hesitate to say yes to a thru-hike is because they can be very expensive. If you want to thru-hike a long trail like the Appalachian Trail or Pacific Crest Trail, you should save at least $5,000; $10,000 would be better. While thru-hiking, you can’t work, and you have to buy food, pay for hotels, laundry, sending packages, going to the doctor, and more. You’ll also need to purchase gear, which can cost another $1,000 to $2,000.

Most states won’t allow youth to work until they are 14 years old, but there are ways to start making money when you’re younger: babysitting, mowing lawns, shoveling snow, yard work, dog walking, pet sitting, and more. Once you’re old enough to work, find a job and learn how to save money.

If you are 14 years old, and you want to thru-hike after graduating from college at age 22, you’ll need to save $1,000-1,500 a year specifically for your hike. You’ll have many other expenses in life too, so learning how to balance a budget and save money is crucial. This is also an important skill for your hike. One of the main reasons people end a thru-hike early is because they run out of money.

When to thru-hike

If you plan to thru-hike one of the long trails in America, you will need four to seven months. Once you move out on your own and start working a full-time job, it is very difficult to quit a job and go thru-hiking. Not impossible, but harder.

If you want to go immediately after high school and plan to go to college, you’ll have to delay your college start date by a semester, or even a gap year, which is taking a year off between high school and college. Delaying your college start date may make your parents really nervous. Developing a specific plan, and making sure you’re accepted to college, and your college or university will allow you to take a gap year without losing your place, may calm some of your parent’s fears.

If you delay your college start date by one semester, you still won’t be able to start your thru-hike until after you graduate high school, so you’ll probably need to do a southbound thru-hike on one of the National Scenic Trails for weather and safety reasons.

While you’re in college, build up your backpacking experience by thru-hiking a shorter trail of a couple hundred miles, which can be done during your summer break. There is even one college that allow students to earn college credit by thru-hiking. Maybe there are more?

Another good time to thru-hike is immediately after graduating college before starting your first job, or after graduating and working for a while to save up money. In fact, this is the most common age group to thru-hike the Pacific Crest Trail, according to the Halfway Anywhere blog. Fewer than 2 percent of 2019 PCT thru hikers were younger than 20. About 30 percent were between the ages of 25-29.

More questions?

If you have any other questions about how to start planning a thru-hike, please leave a comment below. I found magic out there, and I will do whatever I can to help you find that magic too.

Backpacking Skills for a Pandemic

Backpackers are a tribe of MacGyvers, experts at “embracing the suck” and rationing toilet paper. Has anyone else been thinking about all the ways our backpacking skills could become useful during this pandemic?

Here is my list, mostly humorous, a touch of serious. I’d love to hear from all you MacGyvers out there. What backpacking skills are you using during this pandemic? Leave a comment below.

Rationing toilet paper

If backpackers earned badges like Boy and Girl Scouts, there’d be one for successfully rationing toilet paper. There is a very specific flavor of panic when you’re halfway through a backcountry trip, still 40 miles from civilization, and you pull out your Ziplock baggy of toilet paper and realize you’re running dangerously low. Engage radical rationing!

Andrew Skurka, famous for his C2C route and route-finding his way through Alaska’s Brooks Range, only rations himself four squares of toilet paper a day. Four!

When the worst case scenario happens, and you forget your toilet paper on the bedside table while packing up your gear, or at the last cat hole five miles back, backpackers learn with a quickness which broadleaf plants to use like large-leaved aster and thimbleberry leaves. There are even those who’ve claimed to have used a rock. Seriously? Ouch!

If this shortage of toilet paper continues, or gets worse, I have no doubt Andrew Skurka will end up hailed as a national hero for demonstrating how to execute a backcountry bidet. You’re welcome, America! The last thing we need during the coronavirus pandemic is a simultaneous epidemic of monkey butt.

Where’s my duct tape?

We’ve washed our clothes in buckets and bathtubs. We’ve duct-taped our broken tent poles. We’ve used safety pins to hold together our pack. We’re experts at sewing up our shoes with humble dental floss, and having it hold for days until we get to the next town. We are a tribe of MacGyver’s. I’m not sure exactly how, yet, but I know this skill is going to come in handy at some point. Already MacGyvered something related to the pandemic? Share your genius in the comments below!

We eat, literally, anything

When hiker hunger sets in, backpackers don’t care how food tastes or looks or even smells. Food is fuel.

We’re experts at eating the same thing over and over and over. I ate tortilla-Nutella-dried apricot wraps almost every day for four and a half months on my North Country Trail hike.

Dang! I really wish I’d gotten some Nutella and apricots on my last grocery run. I did buy a ton of Snickers bars “in case things get really crazy.” They’re my ultimate back-up survivor food, apparently.

Many of us may have a sizable back stock of dehydrated foods too, just in case things get extra crazy. By the way, if you haven’t done so yet, look way, way back in your kitchen cabinets. I promise you there’s a long forgotten bag of dehydrated potatoes or a lonely package of ramen back there. I have a can of NIDO powdered milk that is big enough to last me at least a year. It’s fortified!

Experts at social isolation

Social distancing isn’t that bad when you’re used to extended periods of social isolation. Anyone who backpacks solo for extended periods of time:

- Knows just how weird you get after a 10-day stretch in the backcountry without cell phone service or seeing another person,

- Has had lengthy conversations with squirrels or other animals,

- Knows how it feels to go so long without seeing another person that, when we finally do see one, we startle like an animal and jump like we’re about to sprint off into the woods.

We’ve spent so much time alone with our thoughts that we’ve come to profound realizations about our character defects that unravel everything we’ve ever known about ourselves. Burn that ego to the ground, baby!

By comparison, I feel wealthy in social connection during this pandemic. My social media network has never been pithier, nor more supportive. I’m video chatting with friends regularly. We even got a game of Cards Against Humanity going online last night. I’m writing this blog, and hope to do an online hiking presentation next week for kids distance learning at home. I’m bringing the field trip to them! The ways in which all of my communities are staying connected is a wonderful thing to behold.

Hand sanitizer hygiene

We’re totally comfortable with trusting hand sanitizer to keep us from getting sick, and also incredibly good at rationing it.

On the topic of hygiene, much of America is probably testing their personal limits for how long they can go without a shower right now. We already know. We know the exact perfume of our own body odor. We can’t even smell it anymore, can we?

Admit it. We backpackers happily stopped showering at a “socially acceptable” level weeks ago.

Mother Nature is in charge, always

Backpackers have watched winds bend old growth trees like prairie grass. We’ve lain in our tents with lightning striking all around us. We know the ferocious power Mother Nature can unleash in a heart beat.

Humans have never been at the top of the food chain on this planet; viruses have. And we’re learning just how ferocious their particular power can be right now.

One of the most important backpacking skills is learning to accurately and quickly assess conditions. Insane straight-line wind storm moving in overnight? Time to get off the trail. Twenty-thousand-acre forest fire? Find the next stretch of trail that isn’t currently burning. Extreme risk of avalanche? No crossing that mountain pass for now.

Covid-19 is a viral wild fire, a microscopic avalanche. Conditions have changed. This is our wheelhouse, backpackers. We must accept the current conditions out there, radically and quickly.

Embracing the suck

The world sucks right now in so many ways, but we backpackers know how to put our heads down and keep moving through the misery, don’t we? We know the value of grit and perseverance.

Backpackers encourage each other to “embrace the suck,” from brutal weather to difficult trail conditions and even physical pain.

This pandemic isn’t Type 2 fun, something that is miserable while it’s happening, but ends up being a great story later. I fear we have some Type 3 situations coming soon — terrible when it’s happening, and terrible to talk about later — but I hope that if we all embrace the suck, and keep working together, we could be part of one of the most epic hero stories humanity has ever told.

After 2,000 miles, my body makes more sense

During my long hike on the North Country Trail, I lost 30 pounds. When I returned home, I found myself able to run 7 miles without difficulty. I’ve never run 7 miles in my life. It felt like magic.

Before I started my 1,500-mile trek, I anticipated going through major physical changes. Hikers talk about getting your “trail legs” after you’ve been hiking for a few weeks. It’s true that your legs get incredibly strong during a long hike, but your stamina, heart, abs, back, and arms all get stronger too. Your whole body fortifies itself for this long, long walk.

I didn’t anticipate feeling like I’d unleashed an ancient physiology in my body.

Ancient ability

I’ve done two long-distance hikes for a combined distance of more than 2,000 miles. I’ve become convinced that long-distance backpacking mimics something every human body is capable of doing: migrating huge distances.

In history class, when I learned about the people who walked across the Bering Strait or paddled across the Pacific Ocean, I couldn’t identify with those ancient peoples. They felt like a different species of super human.

Now I know that those ancient people were doing something well within our abilities as a species. My body is not just capable of hiking 1,500 miles, it was built for that purpose.

Until about 11,000 years ago, humans were hunter gatherers. We followed our prey, migrating long distances frequently. Some modern day humans are still hunter gatherers, but most of us switched to agricultural societies about 10,000 years ago. Although we settled into more stable communities, we’d still spend our days physically working to cultivate and raise our food.

Our shift to a more sedentary lifestyle is only a couple hundred years old, intensified by our nearly total modern dependence on motorized vehicles. I live in a time and place where it is entirely possible for me to get up from my bed, drive to my job, and stop at the grocery store on my way home without actually walking very much at all.

My body seems much happier on trail.

Sleeping, Homo Erectus style

I never have trouble sleeping when I’m backpacking. Hiking 15-20 miles in a day is exhausting, which makes sleep come fast, but I think there is more to my easy sleep than just physical exercise.

I get all sorts of interesting reactions from people to my hike. Recently, someone asked me, “But isn’t it really dark in the forest, like, true dark?” Yes, it’s really dark in the forest. I miss the “true dark” every day.

As night falls in the woods, free from the blue light of a high-def TV or smartphone, away from the searing brightness of LED street lights, the natural change in light seemed to trigger a release of melatonin so strong that I’d feel like someone had slipped me a sleeping pill. Some nights, I’d literally be falling asleep as I ate dinner. I remember being annoyed in my tent on full moon nights because the light felt too bright.

After walking so far in a single day that I was worried I’d fractured my feet, I’ve also come to appreciate that sleep is actually a miracle drug. I would fall asleep, legs and feet throbbing, and wake up with brand new feet, my legs stiff but fine.

A painful understanding

My tolerance and understanding of pain also changed during my hike. Yes, my feet hurt almost every day for the first three months of my hike. My second week, I was actually worried I’d caused a stress fracture. Okay, my left foot still isn’t totally back to normal, but I stopped thinking that all pain meant danger. I started to extend my pain limits. I also realized that I was healing even as I continued to hike. I might have a series of days of knee pain, but as long as I didn’t push too hard, I could still hike pretty far. I could keep moving, and after a couple days, the pain would subside.

Food is fuel

My relationship with food completely changed. In “regular life,” I have to be very careful about avoiding sugar and fat, and get a lot of exercise, or I start gaining weight. In my off-trail life, I fight a constant battle with food. On trail, food is fuel. By the end of my hike, I cared little about how things tasted, and much more about how they impacted my energy level. I discovered fat was essential to maintaining a high energy level. This Outside Magazine article about a Colorado Trail thru-hiker’s metabolic changes supports what my body was telling me: fat is the best energy source for hiking.

Heightened senses

Of my five senses, I use my eyes the most in my city life. In the woods, my hearing and sense of smell became equally important.

A well-known phenomenon often discussed by backpackers and thru-hikers is how pungent day hikers become after you’ve been hiking for a while. When you pass a freshly bathed day hiker, the perfume of the soaps and shampoos still on their skin socks you right in the nostrils. It’s shocking, and a nice break from your own garbage stench.

Hikers have all sorts of theories about why this happens: the air is cleaner in the forest so our olfactory system clears out; the smells of the forest are more subtle so day hikers just seem more fragrant by comparison.

The change in sensitivity of my sense of smell was so sudden and big when I returned to the forest that I suspect the change is actually rooted in our mind.

I think our brain turns up our sense of smell in the woods. I could cross paths with a day hiker, be pleasantly overwhelmed by his or her clean scent, and then hike into town and not have the same thing happen my entire town stay, despite crossing paths with lots of clean people.

Just as our brain edits out all sorts of unnecessary information from our eyes, I think our brain turns down our noses in town because there are too many pungent smells: the sharp, acrid smoke of a diesel truck, hot garbage rotting in the sun, the local restaurant’s fryer.

I think we need our sense of smell more in the forest. My sense of smell became as important to me as my eyesight, especially when the forest was dense and visibility is limited by trees and brush. I usually knew it was going to rain because of my nose rather than my eyes. When I walked into a giant cloud of musk, I would suspect a bear was nearby, even though I couldn’t see or hear it. I would hike on alert until I was well past the smell.

After a couple months on trail, I noticed that when I heard a loud noise, I’d turn my ears toward it instead of my eyes. Again, in the dense forest, my ears will usually give me more accurate information. Is whatever is making the noise moving away from me or toward me? Is it big or small? Does it sound like an animal or a tree branch falling? I was delighted how turning my ears toward a sound seemed to become instinctual after a couple months.

My hearing also got much more sensitive. Or, rather, my reaction to loud noises heightened. This hasn’t gone away with my return to the city. The other day, I was walking my dog and a fire truck drove by us on the street. I found myself covering my ears because the volume of the siren actually hurt.

Humans are animals

As I more fully used all of my senses, I started to think and feel more like an animal.

My startle response lowered. Instead of jumping out of my shoes when a grouse exploded out of the underbrush next to me, my body would quickly assess there was no threat, and didn’t even bother turning on my adrenaline. Similarly, when I heard big, loud sounds in the forest, my first reaction wasn’t fear. My body would calmly listen. I could almost feel a subconscious assessment happening in my primitive brain. I felt like my body was carefully guarding my energy reserves until it knew my survival depended on activating its “emergency response system.”

Stinky sweat is nature’s air conditioning

Thanks to long-distance hiking, I now know the sharp, spicy stench of my body after 10 days without a shower or deodorant. I know, you’re probably asking, who ever needs to know that? I don’t know if you need to know it, but I found it disgustingly interesting to know exactly how bad I can smell.

I learned just how important sweat is. When I was waking up in July to 90 percent humidity, I started to actively look forward to being drenched in sweat because the slightest breeze would cool me down so much. It’s only when there is no wind, a truly rare phenomenon in the woods, that being drenched in sweat is annoying.

Being wet also changed for me. Before backpacking, I avoided getting wet in rain storms, or getting my feet wet in puddles as I walked into work. Being damp and wet when you’re sitting in an air conditioned office all day, not moving, is seriously unpleasant. During the height of the summer months, I actively prayed for rain to cool me down. Having to walk through creeks, puddles and mud pits is such a common occurrence when hiking that I don’t even notice it anymore.

The oil our skin secretes also made more sense. Even though I was going without showering for 6-10 days at a time, my skin and hair felt less greasy than back in “regular life” after a day without a shower. My theory? Our skin evolved to cope with being outdoors all day long. When you’re hiking in a constant wind, the oil evaporates off of your skin, protecting it from completely dehydrating, cracking, and inviting infection. When you’re indoors all day, without any breeze, the oil just builds up on your skin and in your hair.

I’ve been shaving my armpits and legs since I was 11 years old. This hike, I decided to do an experiment. I shaved for the first month, but then let the hair grow. I was wondering if leg and armpit hair might serve some previously unknown purpose. Would leg hair help me feel a tick crawling on me faster? Would hair in my armpits help wick away sweat and prevent chafing? No and no. My skin is so sensitive, I sensed ticks just fine with and without leg hair. And in chafing season, armpit hair made no difference.

Conundrum: Ancient bodies in modern times

After 2,000 miles, I know my body was not built to sit at a desk all day. When I do, a malaise seems to set in, a near constant fatigue. After working at a desk all day, I often feel too physically exhausted to go to the gym, even though I haven’t actually moved all day. When I sit or nap all day, all I want to do is continue sitting and napping. Our bodies seem to have a physical inertia.

I’m prone to muscle tension in my neck and head, and migraines when I’m being more sedentary, but not on trail.

Coming to this new understanding of my ancient physiology is one of the most challenging ways that long-distance hiking has changed me. It’s nearly impossible to reproduce this ancient way of life in modern society. Even going to the gym several times a week, or for several hikes a week, can’t replicate the amazing effects of long-distance hiking. My job skills are still best suited to an office setting, so I’ll likely end up working at a desk again. Aside from completely changing my career path, I can’t see a way to be physically active all day while earning a living wage.

Instead of returning to a sedentary life in the city, I’m hoping to move closer to the north woods. If I can, I’d like to live close enough to my work to be able to walk, run or bike my commute. My post-hike goal is balance: I need to return to work, but I want the woods to be a daily part of my life.

This is one of my favorite conversations to have with other hikers and backpackers. Have you noticed any differences in the ways your body performs in the woods compared to “regular life”? Leave a comment below!

Beaver fever SUCKS

My final morning on trail, I sat in my tent with the bug screen and rain fly open. Nausea and stomach pains roiled in my gut, and I was trying to make a decision about whether to continue west on the trail, or head back east to the safety of a cheap bunkhouse at Gunflint Northwoods Outfitters.

As I sat there, a pack of wolves started howling very close by. I looked west at the low ridges along Howard Lake and felt sure the wolves were just on the other side. I’d never heard wolves howling so close before.

After deciding to head back east, my fatigue and weakness were bad enough that I really hoped those wolves didn’t decide to come hunt in my direction. With my physical condition weakened, I felt even more vulnerable than usual to the carnivores of the Northwoods. I’ve never harbored any fantasy that I could fight off a pack of wolves. I’ve always counted on their avoidance of humans. My most genius plan, and I always knew it was more a fantasy than a realistic survival strategy, was constantly scanning the woods for climbable trees.

I haven’t climbed a tree since I was a kid. After puberty, my upper body strength evaporated and now I can barely do five push ups.

As I hiked that final morning, waves of nausea and dizziness washed over me, and I felt a deep empathy for the sick and aging prey of the forest. How terrifying it must be for a deer to have Chronic Wasting Disease, and feel their ability to run and defend themselves also waste away.

Every experience in the woods, even the ones that involve explosive diarrhea, can teach you something new.

Weeks after retreating home to my mother’s house in the Twin Cities, I finally found out why I was sick: giardiasis, a.k.a. beaver fever. “Giardia is a microscopic parasite that causes the diarrheal illness,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “(…)While the parasite can be spread in different ways, water (drinking water and recreational water) is the most common mode of transmission.”

The CDC lists a few common ways to get giardia: backpackers who drink untreated water, making contact with animals who have the disease, making contact with people who have the disease, and more.

If ever diagnosed with giardia, you may get a call from your state’s Department of Health, as I did. That’s how I learned it’s possible to get giardia from swimming or wading through contaminated water sources as well. Due to cold temperatures setting in at the end of August, I hadn’t been doing much swimming, but I was still doing lots of wading through flooded areas. The Arrowhead in Minnesota got a lot of rain in September, and beavers are always hard at work.

Symptoms of giardiasis usually present 1-3 weeks after infection. The Minnesota Department of Health had me list my previous three weeks of waters sources. It was a long conversation involving maps and guides, as I’d filtered water at least 2-3 times a day from backcountry sources.

I’m not sure how I got beaver fever.

I was very careful when I filtered to avoid getting “dirty” water in my clean water bottles, but accidents happen. When temperatures started to get near freezing at night, I’d put my water filter in a plastic bag and tuck it at the bottom of my sleeping bag to prevent it from freezing, but maybe I forgot one night.

I also hiked with someone during that period who believed they had giardia and took medication just before hiking with me. It’s possible I got it from people-to-people contact. I’ve decided during future long-distance trips, I will avoid hiking with anyone who is currently sick or has been sick recently.

Here’s what I can tell you about giardia: IT SUCKS. Big time. It sucks so bad that if I ever get to do a long-distance or long-term outdoor adventure again, I will make sure the medication (tinidazole) for this parasite is in my medical kit before I leave. I had a surprisingly difficult time finding a pharmacy that had tinidazole in stock, likely due to the fact that this disease isn’t very common anymore in America.

The CDC says some people don’t experience symptoms. Lucky dogs. Here are the symptoms I experienced:

- Bad stomach ache

- Nausea

- Extreme bloating and gas (That smelled extremely bad, like rotten eggs and sulfur)

- Diarrhea

- Complete loss of appetite

- Inability to eat more than a few bites of food at a time

- Fatigue

- Weight loss

I’m being dramatic now, but I swear I could feel these little bugs inside my gut. I felt like aliens had taken over my digestive system, and broken it.

Getting treated for this illness was its own challenge. The first test my doctor performed for the parasite came back negative. Apparently, this is normal. Multiple tests over multiple days must be done. It was my second test that came back positive, and finally got me the medication I needed. My health insurance didn’t cover tinidazole, and I had to wait 10 days for a special approval.

On the Appalachian Trail, thru hikers seem to expect a bout or two of norovirus. Somewhere in all of my backpacking research, I’d gotten the impression that giardia wasn’t much worse than norovirus, which usually lasts 1-2 days. I was really wrong. Not only can giardiasis symptoms last 2-6 weeks, without treatment, symptoms can come back, according to the Mayo Clinic.

Beaver fever may sound funny, but it sure doesn’t feel fun. I feel bad for any beavers out there with giardia who are trying to build a dams or chew down a poplar tree. They’re having a rough day, I can tell you.

Less than halfway, but proud thru and thru

On Sept. 26, I didn’t know when I set up camp at Howard Lake on the Kekekabic Trail that it would be the final night of my hike.

The week before, I’d had beautiful, mild weather on the Border Route Trail with temperatures in the 60s and 70s. Plenty of sunshine kept my spirits high, along with having the company of Michelle Schroeder, and getting to meet up with Patty and Dave Warner for the first time since Michigan.

Just as I finished my last blog post, Dave and Patty walked through the front door of the historic Clearwater Lodge. I gave them hugs, and gratefully accepted their offer to take me to lunch all the way down in Grand Marais, a 45-minute drive down the Gunflint Trail, so I could also get a new tent. The waterproofing treatment I’d given my rain fly hadn’t done the trick. I’d lucked out so far, weather-wise, but the forecast showed temperatures would be dropping into the low 30s as I headed onto the Kekekabic Trail, and there was plenty of rain in the forecast.

Patty, Dave and I ate pizza at Sven & Ole’s in Grand Marais, and caught up on the last two months we hadn’t seen each other. They’d just finished a two-week trip in the Boundary Waters. Our original plan had been to meet inside the vast wilderness area at Agamock Lake, but I’d moved too slowly up the Superior Hiking Trail. Once again, Patty and Dave’s good company and kindness gave me a boost in morale, and helped me solve a major gear issue.

New tent in hand, I returned to the lodge after the too-short visit with Dave and Patty, and found the room I was sharing with Michelle was cleared out of her gear. She’d left a note explaining she’d decided to head back out to the trail so she could hike all the way to the western terminus of the Border Route Trail. Her time was more limited than mine.

Michelle’s sudden departure was a bit jarring at first, like finding a “Dear Jane” letter. I wondered if my stench had driven her away, chuckling to myself. I admired her determination to finish as much of the BRT as she could. I realized I’d be hiking solo in the Boundary Waters for the first time, the eventuality that had so spooked me in Grand Marais that I’d stalled out for three days. Instead of fear, I felt excited to finally get to get some alone time in my favorite place on earth.

I headed out the next morning and had a perfect day of hiking. The first five miles from Clearwater Lodge to Rose Lake passed quietly beneath sunny skies, through woods perfumed by leaf litter. At the end of “The Long Portage,” I took a short break to enjoy the breathtaking view of the palisades on the Canadian side of the lake. I’m not sure what alchemy exists between lake and sky at Rose, but it always has the best clouds.

The trail climbed up from the lake shore onto the ridges high above, where I came mere feet from stepping on a porcupine, hidden from view by thimbleberry bushes growing along the trail. I backed up, and watched the porcupine watch me. It seemed nonplussed by my presence, neither scared nor aggressive. Every time I get to have a close, benign encounter with wildlife, I’m grateful, and this porcupine was an especially gorgeous specimen with glossy black fur and a mohawk of yellow-tinged quills running down its back.

I ate lunch at the Stairway Portage Falls, taking a little extra time to enjoy the view and a cup of coffee as I’d already hiked 2/3rds of my planned mileage for the day. One way that I dealt with my fear of hiking the Border Route and Kekekabic Trails solo was to plan shorter days. The Border Route Trail was in such good shape that it really hadn’t been necessary. I decided to make it to the spur down to South Lake, and then decide if I wanted to keep going.

I had vivid memories of losing the trail in 2017 for a full half hour after the Rose Lake Cliffs and Spire vistas. Between the forest fires of 2006 and 2007, and the derecho straight-line wind storm of 2016, the trail had been extremely difficult to hike and follow from this point west.

A couple of upturned root balls alongside the trail was the only remaining trace of the destruction I’d often described as being like a bomb had gone off in the middle of the wilderness. Campsites that had been closed in 2017 were open again. I reached the South Lake spur early, the day was gorgeous and my body was singing, so I kept hiking to Sock Lake.

My night in camp was perfect too. I arrived around 6 p.m. Pitched my new tent without issue, and cooked dinner on the rock outcropping over the lake as twilight descended. The still waters of the lake perfectly mirrored the forest on the far shore. The peace and quiet stole into my soul. And because the sun is setting so much earlier now, I was awake late enough to see the Milky Way for the first time since I was a child.

With the trail in such good shape and only 12.5 miles to go to the turn off for the Gunflint Lodge, where I’d mailed another resupply, I suspected I’d get to the resort a day earlier than planned. This would be the first time I’d gotten somewhere earlier than planned my entire hike.

I had a leisurely morning in camp, thoroughly enjoying the sunrise over Sock Lake along with some oatmeal. I would be exiting the Boundary Waters in just a few miles when I reached the Crab Lake cut off trail. I wanted to savor the beauty of the Boundary Waters, but knew I’d get more on the Kekekabic Trail too.

As the trail neared Gunflint Lake, I braced myself for the brush to make navigation difficult. During my previous hike of this trail, the brush was so overgrown that my dog couldn’t even find the trail with his nose. On the western 12 miles of the BRT, forest fires burned back the forest, allowing brush and young trees to claim the space. The brush of 2017 ultimately ended that hike early as my hiking partner wrenched his knee so badly on an unseen rock that we had to ditch out on Loon Lake Road.

I had no issue this year with the brush, a product of trail maintenance, and also hiking in late September versus mid-July. The brush was already dying back from cold nights.

I hiked down the short spur trail to Bridal Falls, which were running pretty low despite the near constant rain the area had received since late August. Before long, I reached the crossing of Loon Lake Road, and headed onto a new stretch of trail. The stretch on top of the Gunflint Cliffs was amazing hiking. As I reached a vista, I realized I was looking down on the Gunflint Lodge, where I was heading for the night. If I’d had any rock climbing skills, I could’ve just scaled down the 200-foot cliff, but I don’t.

One of my favorite parts of hiking the Border Route Trail is that it gets you up on top of the ridges you see when you canoe through this area of the Boundary Waters. I’ve wondered so many times what it’s like up on those palisades and cliffs. Now I know; it is the domain of raptor, where hiking feels more like flying, where the winds are stronger out of the cover of the forest and the water far below.

I climbed down from the cliffs and started navigating through a maze of ski trails, which BRT hikers often report can be tricky, but all the junctions were well marked and easy to follow. I had no difficulty. I did notice that the Gaia GPS map of this section of trail between Loon Lake Rd. and Cty Rd. 20 was wrong; it shows the trail running below the cliffs, not on top of it. I trusted the trail signage instead of my app.

I reached the lodge by 6 p.m. I probably should’ve realized something was up with me when I didn’t immediately go eat a cheeseburger. I didn’t bother eating dinner at all that night.

I cannot sing Gunflint Lodge’s praises enough. On two separate hikes, they have not only been willing to hold resupply boxes for me, offer $18 bunkhouses (cheaper than many campgrounds where I stayed on this hike), they’ve also been genuinely excited by my treks. Way back in Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore, I’d met an awesome group of Boy Scouts and discovered one of them, Cameron, would be working at Gunflint Lodge for the summer. “I’ll see you in 1,000 miles,” I’d said.

“Cameron is going to be so mad that he missed you,” Dana told me, another employee at Gunflint. I was disappointed I’d missed Cameron too, but thrilled to hear I was missing him because he was on a canoe trip in the Boundary Waters.

I picked up my resupply box from Dana, a BWCA permit for the Kekekabic Trail, and turned in early. The next morning, I finished the remaining 6.5 miles of the Border Route Trail, which took me past Magnetic Rock, which set my compass spinning all directions except north. The weather had changed the evening before. Gone was the warm sunshine; in its place, blustery winds drove patchy rain clouds in waves above, periodically blocking the ever weakening sunshine. When the sun was out, I could hike in my T-shirt. The second the clouds covered its light, the temperature dropped ten degrees. My day became an annoying game of putting layers on, then taking them off, then on, then off.

I was having a great time, but a stomach ache was dampening my mood a bit. It wasn’t uncommon for me to have a small tummy ache on trail; usually they just signaled to me I could expect to be digging a cat hole within the next mile. But this one strengthened throughout the day.

I crossed the Gunflint Trail, walked the tenth of the mile south to the eastern Kekekabic trailhead, and hiked the first three miles to a campsite on Bingshick Lake. For the first time since late spring, I chose a tent pad out of the wind as a cold breeze was gusting in from the lake. I cooked a big, hot dinner, despite having no appetite and turned in. After hiking 1,500 miles, it’s a peculiar feeling to not be hungry. Hunger becomes a constant companion, something to which you just adjust as being part of your daily life. Eat a Cliff bar, get 15 minutes without hunger. That’s about it.

Around 7 p.m., tucked cozily into my down quilt, an animal suddenly sprinted past my tent toward where I’d hung my food bag. For the first time on my hike, I grabbed the pepper spray I keep in my tent; I was convinced it was a bear. Almost dark, the thought of other humans coming into camp didn’t even occur to me. The animal ran back toward me. My heart was pounding. Then I heard voices. Relief flooded over the adrenaline as the group hiked past to another campsite down the trail. The sprinting animal was their dog.

I headed west on the Kekekabic the next morning toward Chub River and the Seahorse Lake narrows, a stretch of trail that in 2018 actually made me yell in frustration because I found it so difficult. The brush and rocks along this stretch had been exhausting. But like the Border Route Trail, the Kekekabic was in amazing shape. I, however, was not.

I struggled down the trail not because of trail conditions but because my stomach ache had gotten much worse, and was now being accompanied by severe nausea and stomach pain. Fatigue slowed my pace to a crawl. I took lots of breaks and tried to force myself to eat, but when I’d only made it five miles by lunch, I decided to set up camp early at Howard Lake. I hoped that eating a lot of food, and getting lots of sleep would make me feel better.

I spent the day reading and eating, soaking in the true peace and quiet of the Boundary Waters, which I’d entered again just before Bingshick Lake. I cooked a Camp Chow Chili Mac meal, even adding some cheesy instant potatoes, and forced it down. This may go down in my memory as the worst meal I’ve ever eaten, not because the food was bad, but the nausea was so bad that I wanted to vomit every other bite. On trail, there is little that can be done to make yourself feel better besides eating and sleeping. I tried both.

The next morning, I slept late, waiting out a cold rainstorm. I didn’t feel better, but I also didn’t feel worse. My stomach hurt, and I couldn’t eat. I sat in camp, trying to decided whether or not to keep going west, or turn back to Gunflint Lodge to wait out this illness. To the east, help was at least 30 miles away to the first resort, and about 50 miles until the town of Ely. The Gunflint Lodge was only 8.5 trail miles and a couple road miles behind me. As I sat and struggled to make a decision, a pack of wolves started howling nearby. I sat, enthralled, guessing they were within a half a mile. I’d never heard wolves so close.

I decided to backtrack to Gunflint Lodge. At no point during my 1,500 mile trek did I feel I was on a forced march. I did that final morning. Every step I took was in service to getting myself off this trail, nothing more. I felt terrible, waves of stomach pain and nausea getting worse. I couldn’t eat at all. My body switched on whatever reserves it keeps for emergencies and got me off that trail.

When I reached the lodge, I called my mom to alert her to my change in hiking plans. When I’d checked back into the bunkhouse that Friday, staff let me know the outfitting side of the lodge, which operates the bunkhouses, would be closing the following Monday. I had two days to figure out if I could keep hiking. One positive of being forced off trail by my illness is that Cameron was back from his canoe trip when I came back to the resort. We got to meet up again, 1,000 miles down the trail!

That night, the temperature dropped below freezing for the first time. I was indoors, but the bunkhouses are unheated. Wearing my warmest layers, I could not stay warm. My feet were like blocks of ice. I still couldn’t eat, and around 3 a.m., I woke with an explosion of pain in my gut. I sprinted up the hill to the communal bathrooms, barely making it in time. I spent the next 36 hours in major distress, and wishing for some adult diapers.

Sunday morning, after having a horrifying and simultaneously humbling overnight of incontinence, I decided to go home. The bunkhouses closed the next morning, and I was getting worse. The idea of trying to find other accommodations nearby felt exhausting, much less returning to a trail that runs 40 miles through wilderness in cold, wet conditions. Snow was in the forecast. How could I hike if I couldn’t eat? How could I stay warm?

I knew my hike was done for the year. And I was proved right by the length of my illness once at home. Whatever illness I picked up was not a garden variety upset stomach. I’ve been sick for more than two weeks, unable to even write this blog post. I went from being in the best physical shape of my life to struggling to walk my dog for more than a mile on nice, easy sidewalks. In the time I’ve been sick, the first heavy snows of the year arrived where I’d been hiking.

I learned today that a dehydrated PackIt Gourmet meal I ate on the Border Route Trail, the Big’un Burrito with Fajita Chicken, was recalled Oct. 9 due to possible Listeria contamination. I’m not sure yet that this meal is what made me sick. The company is saying no confirmed cases of illness have been reported to the USDA. I have a doctor’s appointment Wednesday when hopefully I can found out more.

I’ll confess, this was not the dramatic ending I’d envisioned when I set off on this journey five months ago. But I am not discouraged or disappointed, far from it. One thing the woods taught me very quickly is acceptance. Acceptance of the rain, the heat, the mud, and the bugs. The woods also eventually taught me to accept my physical limits, although I fought it. I couldn’t tell if I was failing to hike my mileage goals because of physical limits or a failure in mental fortitude. This time, I listened to my body, gave it a few days to talk to me, but ultimately accepted I couldn’t continue when that became clear. I didn’t beat myself up. I didn’t doubt my judgment. I count that as a win. A loss would’ve been continuing down the Kekekabic in an effort to protect my ego and getting myself into a worse situation.

I’m proud of my failure to hike half of this trail because hiking 1,500 miles just doesn’t feel like a failure. Those miles took everything I had. I met the greatest people. I saw incredible beauty. I made the woods my home for five months, and the woods welcomed me.

Every long distance hike is a question: Can I do this? I’ll write more in-depth on this soon, but after reading and watching so many people thru-hike other National Scenic Trails, I wanted to find out if there was some specific lesson to be learned by hiking 2,000+ miles. For me, there wasn’t. For me, distance is not the most important part of a long-distance hike or a thru-hike, it’s time. I think this is the real difference between thru-hiking and week or weekend trips.

This story is not over. I plan to write more about how this journey changed me, what I learned, and what my re-entry back into city life is like. I want to write some practical things too, tips for other long-distance hikers coming after me, a post about my gear, and an analysis about why I think I failed at hiking half the trail in a single season. Alex, my video editor, and I still have 700 miles of video to edit and release, which I hope to do more frequently now that I’m off trail.

I hope to pay forward all the trail magic gifted to me. I want to help other hikers of the North Country Trail. I want to join trail maintenance trips, paint blue blazes, lop brush, follow the buzz of a Sawyer down the trail and help clear downed trees from a path that now means the world to me. Once I find a new job, I plan to donate regularly to the trail. I want to be one of the thousands of people who are determined to see the 2,000 remaining road miles turned into trail miles.

So here comes the part where I finally ask for money, but not for me. To celebrate the end of my hike, I’d like to do a fundraiser to thank the North Country Trail Association and its chapters.

In total, I hiked 1,506 miles of the North Country Trail. My hope is to raise $1,506 for the North Country Trail Association, $1 for each mile I hiked. If you’ve enjoyed following my hike, reading this blog and watching the videos, please donate by clicking on the link below. In the “Comments” section of the donation page, please write “Annie’s hike”. The NCTA plans to track donations so we will know when we’ve reached the goal.

If you’d like to contribute in a non-financial way to the trail, please consider joining your local chapter or volunteering to do trail maintenance.

To all the trail angels who hosted, fed, encouraged and supported me: The moments I shared with you shine in my memory as brightly as the stars in the Milky Way. Your generosity and kindness were the most unexpected wonder I experienced on my trek. From the bottom of my heart, thank you.

To all chapter members and volunteers: Your dedication to this trail was amazing to witness. You’ve inspired me and shown me the joy found in building this trail. Every step I took past a cleared downfall, a confidence marker, a clear blue blaze, a freshly mowed trail, I thanked you in my mind. From the bottom of my (still) aching feet, which ache much less than they would’ve thanks to your hard work, thank you.

To everyone who’s been reading the blog, watching the videos, and sending comments and emails: You made my hike better, less lonely. When I saw something magical on trail, I enjoyed it more because I knew I would get to share it with you. From the other side of the computer screen, thank you.

To my family and friends: Despite all evidence to the contrary, none of you treat me like I’ve lost my damn mind. Despite running away to the woods for months at a time and missing out on important events in your lives, you cheered me on. Your support meant the world to me. I missed you all terribly. I’ve got so many hugs saved up!

And finally a special thank you for my mom: Thank you for taking care of my dog for five months. Thank you for helping keep me safe while I was on trail. Thank you for shipping random boxes to random places. Thank you for always having time to talk to me, even when you’re on literally on your way to “Hamilton” in Chicago. Thank you for driving six hours to the Canadian border to rescue me off the trail. Thank you for preventing my homelessness by allowing me to stay with you while I now look for work. I could not have done this without you. I love you to the moon!

Happy hiking everyone!

A wild rarity

There is a meadow north of Grand Marais that I love on the Superior Hiking Trail. Meadows in the dense transitional forest between the deciduous and coniferous forests of the south and the boreal forest of the north are rare.

The meadow is long, at least a tenth of a mile, and offers an expansive view of Lake Superior, the tiny island of Five-Mile Rock visible off shore.

After losing my nerve in Grand Marais for a full three days, finding this familiar meadow a riot of fall color, a new sight for me, resolved any lingering fears. I may have hiked the SHT, the Border Route, and Kekekabic Trails before, but no trail is ever the same. They change every year thanks to different conditions; they change with the seasons.

I took in the brilliant burgundy of the sumacs contrasting with the yellow goldenrod, and a purple wildflower, the name of which I don’t know yet. The meadow’s beauty made me so glad I didn’t quit. This would be the theme of the week.

My unease with my ability to cope with shoulder season conditions, extended wet and cold, is not gone, but Mother Nature gave me a break this week with sunny weather and high temperatures in the 70s, and lows in the 50s.

Conditions seem to follow a pattern right now: foggy mornings followed by clear, sunny afternoons, and maybe a little rain in the early evening.

After camping at Kadunce River, I hiked down to the Lakewalk, a beloved and loathed part of the trail because it runs along Lake Superior, which forces hikers to walk a mile and a half in loose cobble, hard going.

About a tenth of a mile from the western end, I hit a lake block. The water of the lake is so high, it came right up to the impassable brush of the wetland that runs along its shore here. I’ve hiked this stretch twice before, and had no memory of being blocked before. Is the level of the water higher after our week of rain, I wondered? I tried bushwhacking around, but soon found myself in a bramble patch and backed out. Thwarted, I walked back to Highway 61, and roadwalked to the first road that led back down to the beach, about a quarter mile.

I hiked up the Brule River toward Judge Magney State Park, noting how the fall colors are really gaining strength. The poplars are turning golden, a couple weeks behind the red of the maples. The color change isn’t just happening in the canopy; the forest floor is also a mosaic of reds, yellows, oranges and browns.

I ate a big lunch at the state park and dried out my tent and quilt as best I could. Even with 70-degree temperatures, the strength of the sun has lessened enough that it can’t seem to overcome the humidity.

I met up with Michelle Schroeder, owner of Backpack the Trails LLC, a backpacking guiding service, at the trailhead just south of Hazel campsite, where we planned to camp. Michelle and I connected through the SHT Wild Women Facebook group.

We slogged through two miles of muddy trail, and found three other guys camped out at Hazel, a rarity for this dry campsite. Brad, from Duluth, had a beautiful fire going. Our group talked until 11 p.m. about John and Joe’s thru hikes of the trail, which they were just starting, Brad’s section hike, my long trek on the North Country Trail, and Michelle’s experiences backpacking all over the country, like her recent solo on the John Muir Trail in the Sierra Mountains. We bonded as the smoke swirled around us and the stars came out. I’d been craving a night like this in camp, and had been surprised to find myself solo more often than not.

Michelle turned back for her car after discovering a huge rip in her hiking shoes. Before joining me on the BRT, I encouraged her to get new shoes. “The BRT eats shoes for breakfast,” I said.

I planned to hike a relatively short day to Jackson Creek, and hoped to cross paths with John, a.k.a. Lynx, who I knew from a Facebook post had just finished hiking the Kekekabic and Border Route Trails before turning south on the SHT.

As I took a break near Carlson Pond, a huge beaver pond, I saw John coming down the trail. He reported the BRT and Kek were easy to follow, a little brushy, but overall in good shape, further reducing my fears about hiking these trails. John is averaging 25 miles a day. I confessed my difficulty with hiking more than 15 miles a day. He confessed his difficulty in not charging down the trail, something that frustrated him when he ended up finishing his hikes early. “It gives me a very productive feeling to hike that many miles in a day,” he said.

Ahhhh, I thought, this may be why I’ve never managed to consistently hike longer miles. I don’t feel a sense of accomplishment or reward. I just feel exhausted and harried.

I said goodbye to Lake Superior on Hellacious Overlook, the last vista of the Grey Lady I’ll have on my hike. She’s been my majestic companion since mid-June.

A rumbling thunderstorm cut our goodbye short as a steady rain began to fall. Just before the Jackson Creek campsite, thanks to my quiet hiking, I managed to startle Thad, a backpacker and grouse hunter gathering water from a small creek. He and his wife Lynelle were also camped at Jackson Creek, and on the eve of finishing their years-long section hike of the entire SHT.

Thad and I walked to camp together, stepping carefully on wet boardwalks, but still slipping frequently. In the rain, boardwalks get as slick as ice.

In camp, I set up my rain fly and just sat beneath it for a while, admitting to myself I’m really sick of being cold and wet, doubting that I have the mental fortitude to keep going on this hike should those conditions return for an extended period of time. I ate a quick dinner, set up my tent, and climbed into my dry sleeping clothes and quilt. The bliss of a dry bed after hours of soaked hiking is sublime. I also watched with dismay as hundreds of beads of water formed on the inside of my fly. My waterproofing in Grand Marais hadn’t worked.

The next morning, I packed up my wet tent and quilt, ate breakfast and chatted with Thad and Lynelle, then headed north with just 8 miles remaining of the SHT. On the ridge above Jackson Lake, I met Sean “Shug” Emery, a bit of a backpacking celebrity. He has a huge following on his YouTube channel, almost 90,000 subscribers. He is known and for teaching people about hammock camping, and his prolific hiking here in Minnesota. It’s thanks to Shug that I have a ULA Circuit backpack, a pack I love so much that I’ve had dreams about it. I’ve watched all of his hiking videos, studying his Boundary Waters hiking videos especially close. I’m a fan, and it’d been a hope of mine to meet Shug out on the trail for years. We chatted for 20 minutes, and he was as funny and charming in real life as he is in his videos.

I got to the northern terminus trailhead just before noon, when Michelle and I had planned to meet. After half an hour and no Michelle, I figured she hadn’t been able to make it back to the trail, and decided to cook some lunch before heading out solo. Fifteen minutes later she arrived, apologizing and explaining a problem had come up with the AirBnB rental she operates. With no cell service at the northern terminus, Michelle decided to drive back out to cell service and figure out a way for her to still be able to join me.

I took advantage of the wait to get some camp chores done, sewing up holes in my shoes, getting water, journaling, drying out my gear. At 3 p.m., I realized I didn’t want to hike the five miles to the Portage Brook campsite that night. The last time I’d hiked the eastern 12 miles of the BRT, it’d been so overgrown, I’d only managed a mile an hour. The sun sets at 7 p.m. now. Michelle came back and I proposed we meet 12 miles down the trail at McFarland Campground the next day. I camped at the BRT site on the Swamp River, totally calm and excited to start this 100-mile stretch of wilderness trail.

The next morning, I climbed up to the 270-Degree Overlook, the final northern mile of the SHT and the first eastern mile of the BRT.

At the top, the Swamp and Pigeon Rivers curling silver tracks cutting through the dense forest below, I remembered how ecstatic and sad I was to finish my first thru-hike of the SHT. Although I’ve never achieved the physicality I was looking for on this hike, the growth I’ve experienced as an outdoors woman and hiker was laid bare at this beautiful spot. My legs are corded with muscle, and my lungs and heart their equal match when I’m climbing on trail. My fears are based on experience, not ignorance. My senses are completely attuned to forest life.

In the forest, I am at my fullest potential. I use all my skills: mental and physical.

No trace of fear remained as I turned west down the Border Route Trail. The forest that started this intense journey lay just ahead: the Boundary Waters Canoe Wilderness Area.

My cousins introduced me to this incredible wilderness when I was in my late 20s. I fell madly in love. When canoe trips with them stopped happening every year, I realized I had to go back, even if it meant going alone. I started backpacking, knowing I didn’t have sufficient paddling skills to solo in the BWCA. And I fell madly in love with walking great distances, day after day, and that’s how I got here, walking into the wilderness years later.

After more than 1,400 miles and four months on this trek, one of the revelations that has shocked me is the lack of silence along the trail. I’d estimate I’ve experienced fewer than 10 days on trail when I didn’t hear the roar of some kind of motor, the shock of gunshots nearby, the humming or banging of logging or gas extraction, the sound of traffic on a nearby road.

Truly wild places don’t exist in great number. The Boundary Waters is one of them.

As I hiked the first five miles to Portage Brook, I experienced none of the difficulty of my first hike on this trail. The tread was clear, easy to follow. The hiking felt gentle. None of my fears were realized, and my excitement ramped up. Gorgeous weather made for clear views above Fowl Lake.

I praised and thanked the multitude of unknown volunteers who’ve been working to clear this trail since July 2017. It feels like a different trail.

I strolled into the McFarland Campground profoundly happy that I didn’t let my fears rob me of what may have been one of my best days of hiking so far. As I was settling on a campsite, Michelle arrived, and we settled in for the night. She’d brought manna: fresh fruit!

We crossed into the Boundary Waters the next morning, marveling at the sheer abundance of mushrooms along the trail, and the mind-blowing beauty of the trail.

We hiked to Gogebic Lake, a quiet lake off the popular canoe paths of the area. Campsites on the BRT are often canoe sites, and canoers sometimes don’t share sites like backpackers are used to doing. We had the site beneath cedars and soaring white pines to ourselves, except for a curious Canadian Goose, who joined us in camp for breakfast.

I’m starting to get rewarded for staying on trail so long with new woods knowledge. I didn’t know that white pines drop their needles. The tread is a fresh, plush carpet of needles.

The loons are still on the lakes. The sunshine has become my biggest ally instead of a threat. The bugs and birds hate cold rain as much as I do. I thought the dragonflies were done for the year, but they’re back out again in the warmth, as are a small contingency of mosquitos. I miss the butterflies, though. I haven’t seen one in weeks. My instinctual avoidance of tall grasses due to ticks is easing, and the grasses are transforming from a background plant to center stage in the beauty parade as they go to seed.

Michelle is a great trail companion, offering easy conversation but also an understanding of the value of hiking in silence for long stretches of time. It is a joy seeing her marvel at the beauty of this ancient lake country.

Our hike from Gogebic Lake to Clearwater Lodge offered the full gamut of trail experiences. Socked in by fog in the morning, hiking at 2,000 feet on the ridge above Watap Lake as a thunderstorm rumbled overhead, mist rising thick from the forest, to full sunshine glittering like diamonds on Daniels Lake.

After a rest day, we’ll head back out into the BWCA, back into the wild.

Section: Grand Marais to Clearwater Lodge (SHT to BRT)

Miles: 92.3

Total miles: 1,468.40

Stinky kitty wants to play?

After standing quietly for a minute, not wanting to startle the skunk 30 feet down the trail from me into spraying, I finally called, “Hey, skunk! Coming through!”

I expected this skunk to do what most animals do in the forest when they realize a human is nearby, which is run away.

Not this skunk. It went on sniffing the underbrush like I wasn’t there, and then even started moving toward me. “Is this guy deaf?” I wondered. That would be a bad combination, a deaf animal equipped with a mighty stink bomb. Hikers smell bad enough when we get to town.

The skunk finally realized I was there, but instead of running off, it took in my scent and appeared to be trying to figure out what I was, coming toward me again. Finally it ran away, but down the trail. I followed a far distance behind, hoping I didn’t startle it a few hundred yards later, but I had the prospect of a sub sandwich, pop, as many donuts as I could eat, chips and hot coffee driving me forward. I was out of food and planning to camp at a beautiful site on the Cross River on the Superior Hiking Trail, just a 1.5-mile spur trail away from Schroeder, Minn. and the Schroeder Baking Company.

After a day and a half of rest in Silver Bay, I was eager to return to the trail Sept. 1 for more experiences like with this skunk.

Jeff Asmussen, operator of the Cadillac Cab service, picked me up at 7 a.m. and dropped me back off at Split Rock Lighthouse State Park. I planned to hike to the West Palisade Creek campsite, 20 miles up the trail. But I had a rare moment of cell service and received a text message from Andy Mytys of the Western Michigan Chapter of the NCT. He and two other NCT chapter members, Gail and Doug, were camped out just a few miles up the trail from me.

Whenever I started feeling discouraged by my slow pace, some happy coincidence happens like this to show me I’m exactly where I’m supposed to be. If I’d stuck to my “schedule,” I would’ve missed meeting these guys.

The stretch of trail between Split Rock River and Section 13 is a 35-mile stretch of hard climbs and glorious views. I never get sick of this hard, stunning trail.

I hiked down the spur to the Penn Creek campsite and found the huge, multi group site full of people. I’d only seen a small thumbnail picture of Andy, so I was just going to wander and ask people if they were him, but Gail recognized me first. Greetings and hugs were exchanged. All three of these guys have been following my trek the entire time, and started asking great, specific questions. We talked until after dark.

I was up before dawn, planning a 20-mile day to take advantage of a generous offer from Luke “Strider” Jordan to sleep in the screened porch of his family’s cabin near Finland, Minn.

Andy’s group was up early too, so we ate breakfast together and Andy offered me a bunch of yummy snacks, which I snatched up “faster than a raccoon,” Andy said.